How to Interpret Endoscopies and Colonoscopies from a Functional Perspective

Apr 15, 2025Author: Jeffrey Wacks, MD

Consider the following scenario: a 50-year-old male patient is sent for routine screening colonoscopy. The report comes back that 2 non-cancerous colonic polyps were found and were resected without issue. The patient was advised to repeat the colonoscopy in 3-5 years for continued screening. In conventional medicine, that is the end of the thought process; however, on reflection we might ask, "but why does he have polyps and what does that mean about how his body is functioning?" In reality, a careful inspection of both upper endoscopy and colonoscopy reports can potentially reveal actionable insights that would otherwise be simply ignored.

In our opinion, endoscopic visualization of the intestinal tract can reveal information about the degree gastrointestinal inflammation (see Volume 1 of the training manual for a more in-depth discussion of this foundational concept). GI inflammation can be difficult to prove objectively. One of the best ways of proving GI inflammation is via measurement of gut-specific inflammatory markers in the stool (see Volume 2). However, this can be inconvenient and may be cost-prohibitive for some patients. Otherwise, we often infer the severity of GI inflammation based on the degree of systemic inflammation, clinical symptoms, and presence of other laboratory patterns. Thus, if we can obtain information about the degree of inflammation from an endoscopic report, it can be helpful.

Esophagitis and Gastritis - often referred to as "erythematous mucosa"

When tissue becomes inflamed, it often becomes red, for which the medical term is called "erythema." Thus, endoscopically visualized erythematous mucosa is by definition a sign that the visualized tissue is inflamed. In conventional medicine, erythematous mucosa of the esophagus or stomach (i.e., esophagitis and gastritis respectively) is essentially considered the clinical equivalent of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). H. pylori may be tested, but otherwise, the response to this is to put the patient on an acid blocker. In functional medicine, we would tend to look at the relationship between stomach acid function and GI inflammation holistically. While it is certainly true that acidity may damage tissue (particularly the esophagus), it may also be true that a more foundational inflammatory problem (i.e., SIBO, food sensitivities, etc.) causes dysfunction of the gastroesophageal sphincter, that leads to the hyper-acidic environment in the first place. Suffice to say, endoscopically visualized erythematous mucosa she be thought of broadly as "GI inflammation" as opposed to thinking of it narrowly as "GERD."

GI Erosions and Ulcerations

Gastrointestinal erosions and ulcers represent more advanced tissue inflammation and damage. Erosions are superficial breakdowns of the outer layer of the intestinal lining, whereas ulcers are deeper lesions that penetrate through the mucosal layers. Ulcers may potentially be more consequential as they can lead to bleeding and perforation if left untreated. In general, erosions/ulcerations of the upper GI tract are put into the "GERD" bucket as discussed above. When found in the lower GI tract are generally indicative of "Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)."

Figure 1. An example report of an upper endoscopy in which there was visible "erosions of the stomach" meaning by definition the stomach is significantly inflamed. The only recommended treatment is omeprazole (antacid), demonstrating the emphasis on hyperacidity over controlling inflammation directly.

Intestinal Polyps

A routine screening colonoscopy is generally looking for overt colon cancer or pre-cancerous polyps. Common intestinal polyps (i.e., adenomatous polyps) are generally not thought to be due to inflammation. Gastroenterologists commonly say that the exact cause of intestinal polyps is not fully understood, but factors that may cause them include: genetics, age, smoking, alcohol consumption, low-fiber intake, and obesity. It is well known that patients with IBD have an increased risk of intestinal polyps, but that is classified separately. Approximately 25-40% of colonoscopies find polyps,1 and for the vast majority of these patients without overt IBD, these polyps are not thought to be evidence of GI inflammation. Here, we will summarize why we believe this is wrong. Discovery of routine adenomatous polyps on routine screening colonoscopy is a sign of intestinal inflammation and should be taken more seriously.

Firstly, it is likely that gut-specific inflammatory markers are correlated with adenomatous polyps risk, although the data on this currently is weak. However, a 2008 study by Pezzilli et al.2 showed that fecal calprotectin levels were significantly higher in patients with colonic polyps compared to those with normal colon appearance (17.4 versus 6.0 mcg/g; P = 0.003). Interestingly, in this study the vast majority of patients with colonic polyps would still have a fecal calprotectin within the conventional reference range (less than 50 mcg/g) and thus would be considered "normal" by conventional gastroenterology standards. This emphasizes the idea that in general, conventional medicine sets the bar too high for what they define as clinically meaningful gastrointestinal inflammation. Also, studies show that patients with Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD) have a significantly higher risk of developing adenomatous polyps3 and colorectal cancer.4 We discuss in detail in Volume 1 how MAFLD represents inflammation of the hepatobiliary system, a direct consequence of GI inflammation. Additionally, from a mechanistic perspective, inflammatory cytokines are implicated in the pathogenesis of adenomatous polyps. Specifically, IL-1-beta, IL-4, and TNF-alpha are overexpressed in adenomas.5

Diverticulosis

Diverticulosis is a condition in which small pouches form in the lining of colon (i.e., diverticula). In conventional gastroenterology, diverticulosis is not an inflammatory disease, whereas diverticulitis does represent inflammation and overt infection of these pouches. Diverticulosis is thought to be a structural issue of the colonic wall that is most commonly attributed to a low-fiber diet. But again, whether or not something is fundamentally a sign of inflammation or not depends on how one looks at it. For example, a 2008 study by Tursi et al.6 assessed the mucosal inflammatory infiltrate in different degrees of diverticular disease (asymptomatic diverticulosis vs symptomatic diverticulosis vs uncomplicated diverticulitis vs healthy controls) and found that although neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate was only found in diverticulitis, the mean lymphocytic cell density was proportional to the degree of disease (asymptomatic diverticulosis versus healthy controls, 6.5 versus 4 ; P < 0.02). Similarly, a 2017 study by Barbara et al.7 showed that patients with diverticula, regardless of symptoms, had a >70% increase in colonic macrophages. This also correlated with a difference in the gut microbiome with diverticulosis patients showing a depletion of microbiota members with anti-inflammatory activity. While it is true that studies have not shown a difference in T cells, mast cells, various inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, TNF-alpha), or serum C-reactive protein levels,8 diverticulosis may simply reflect an early stage of pathology, but still ultimately caused by inflammation from a functional perspective.

Additionally, if one considers symptomatic diverticulosis (referred to as symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease [SUDD]), the association with inflammation is even stronger.9,10,11,12 This particular argument might be countered by attributing the inflammation in patients with SUDD to something other than the diverticulosis itself. In the absence of other pathology, we might call that "irritable bowel syndrome" (IBS). However, a 2009 case-control study also showed fecal calprotectin levels were higher in patients with SUDD versus IBS.13

It is also worth noting that from our perspective, the structural integrity of the intestinal wall is highly connected to inflammation as a matter of principle. This is discussed in detail in Volume 1. Thus, it is logical to think of diverticulosis as an early manifestation of gastrointestinal inflammation.

Figure 2. An example report of a coloscopy in which there was significant diverticulosis, an intestinal polyp, and internal hemorrhoids visualized. In conventional medicine, no additional evaluation or management is recommended.

Internal hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids are swollen, enlarged veins in the rectum and anus. They are not thought to be a direct result of inflammation. Rather, the primary cause is thought to be increased pressure in the lower rectum and anus, which is caused by low-fiber diets, straining, and constipation. But again, it depends on the threshold we use to define "inflammation." The rectal vein being swollen and the weakening of the rectal vein wall integrity, implies some degree of inflammation in the micro-environment.14 Patients with IBD clearly have a higher risk of hemorrhoidal disease.15,16 And again, just because patients without IBD also get hemorrhoids, that doesn't mean that subclinical inflammation is not part of the process.

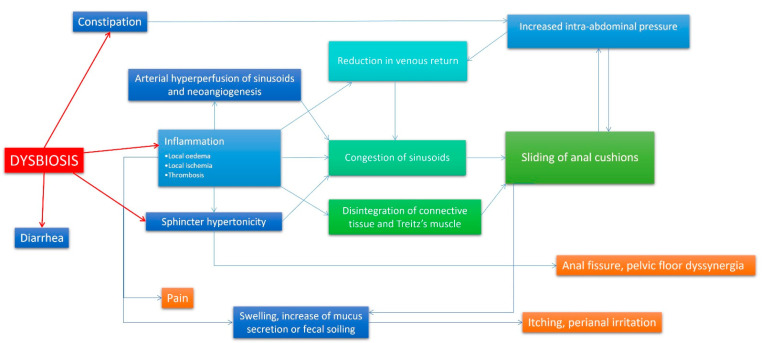

Hemorrhoids generally should be thought of as a holistic gastrointestinal problem. If hemorrhoids are caused by constipation and straining, then why is the patient constipated? In fact, the medical evidence for the importance of the health of the gastrointestinal microbiome in the development of hemorrhoidal disease is well established.17,18 This makes sense as dysbiosis itself will negatively affect gut motility and constipation (see Volume 1). We also discuss the fundamental bidirectionally causal relationship between gastrointestinal dysbiosis and inflammation in detail in Volume 1.

Figure 3. Model of hemorrhoidal disease pathophysiologic mechanism, emphasizing the centrality of dysbiosis and inflammation as root causes.18

Why Does This Matter?

The reason this matters is because when looked at functionally, we can do things to calm down the gastrointestinal inflammation and thus improve the overall bioenergetic function of the system. See Volume 3 for a detailed discussion of the treatment options of GI inflammation. From a medication perspective, those options could include cytoprotective, anti-inflammatory medications such as sucralfate and mesalamine depending on the context. But if one is willing to step outside the box, there are a variety of other anti-inflammatory treatment options, including probiotics, bioflavanoids, serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin, and other cytoprotective/healing supplements. Additionally, we need to think about issues around the microbiome (i.e., intestinal dysbiosis), digestive dysfunction, and food sensitivities, which also contribute to GI inflammation. All of this is ignored by the conventional system as we essentially disregard pathologically benign endoscopic findings that actually do have functional importance.

References

- Cooper GS, Chak A, Koroukian S. The polyp detection rate of colonoscopy: a national study of Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Med. 2005;118(12):1413. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.06.019

- Pezzilli R, Barassi A, Morselli Labate AM, et al. Fecal calprotectin levels in patients with colonic polyposis. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(1):47-51. doi:10.1007/s10620-007-9820-6

-

Yang Y, Teng Y, Shi J, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with colorectal adenomatous polyps and non-adenomatous polyps: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;35(12):1389-1393. doi:10.1097/MEG.0000000000002636

-

Parizadeh SM, Parizadeh SA, Alizade-Noghani M, et al. Association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and colorectal cancer. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13(7):633-641. doi:10.1080/17474124.2019.1617696

- Borowczak J, Szczerbowski K, Maniewski M, et al. The Role of Inflammatory Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Colorectal Carcinoma-Recent Findings and Review. Biomedicines. 2022;10(7):1670. Published 2022 Jul 11. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10071670

- Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Elisei W, et al. Assessment and grading of mucosal inflammation in colonic diverticular disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(6):699-703. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e3180653ca2

- Barbara G, Scaioli E, Barbaro MR, et al. Gut microbiota, metabolome and immune signatures in patients with uncomplicated diverticular disease. Gut. 2017;66(7):1252-1261. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312377

- Barbaro MR, Cremon C, Fuschi D, et al. Pathophysiology of Diverticular Disease: From Diverticula Formation to Symptom Generation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(12):6698. Published 2022 Jun 15. doi:10.3390/ijms23126698

-

Horgan AF, McConnell EJ, Wolff BG, The S, Paterson C. Atypical diverticular disease: surgical results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(9):1315-1318. doi:10.1007/BF02234790

-

Humes DJ, Simpson J, Smith J, et al. Visceral hypersensitivity in symptomatic diverticular disease and the role of neuropeptides and low grade inflammation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(4):318-e163. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01863.x

-

Turco F, Andreozzi P, Palumbo I, et al. Bacterial stimuli activate nitric oxide colonic mucosal production in diverticular disease. Protective effects of L. casei DG® (Lactobacillus paracasei CNCM I-1572). United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5(5):715-724. doi:10.1177/2050640616684398

-

Tursi A, Elisei W, Brandimarte G, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha expression in segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis down-regulates after treatment. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20(4):365-370. Accessed April 13, 2025. https://www.jgld.ro/jgld/index.php/jgld/article/view/2011.4.8

- Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Elisei W, Giorgetti GM, Inchingolo CD, Aiello F. Faecal calprotectin in colonic diverticular disease: a case-control study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24(1):49-55. doi:10.1007/s00384-008-0595-9

- Zhou H, Liu T, Zhong S, Yang W. MicroRNA-770 promotes polarization of macrophages and hemorrhoids by suppressing RYBP expression and monoubiquitination of histone H2A on Lys119 modification. Mol Immunol. Published online April 1, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2025.03.017

-

Wang H, Wang L, Zeng X, Zhang S, Huang Y, Zhang Q. Inflammatory bowel disease and risk for hemorrhoids: a Mendelian randomization analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):16677. Published 2024 Jul 19. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-66940-y

-

Choi YS, Kim DS, Lee DH, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Incidence of Perianal Diseases in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Ann Coloproctol. 2018;34(3):138-143. doi:10.3393/ac.2017.06.08

-

Wang Y, Su W, Liu Z, et al. The microbiomic signature of hemorrhoids and comparison with associated microbiomes. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1329976. Published 2024 May 13. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2024.1329976

-

Palumbo VD, Tutino R, Messina M, et al. Altered Gut Microbic Flora and Haemorrhoids: Could They Have a Possible Relationship?. J Clin Med. 2023;12(6):2198. Published 2023 Mar 12. doi:10.3390/jcm12062198